Out of the 84 individuals that have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics over the last 50 years, only 2 are women: Elinor Ostrom in 2009 for her work on economic governance and just this 2019, Esther Duflo of MIT for her work on poverty eradication and developmental economics.

This begs the question, why are women so underrepresented in economics and why should we care?

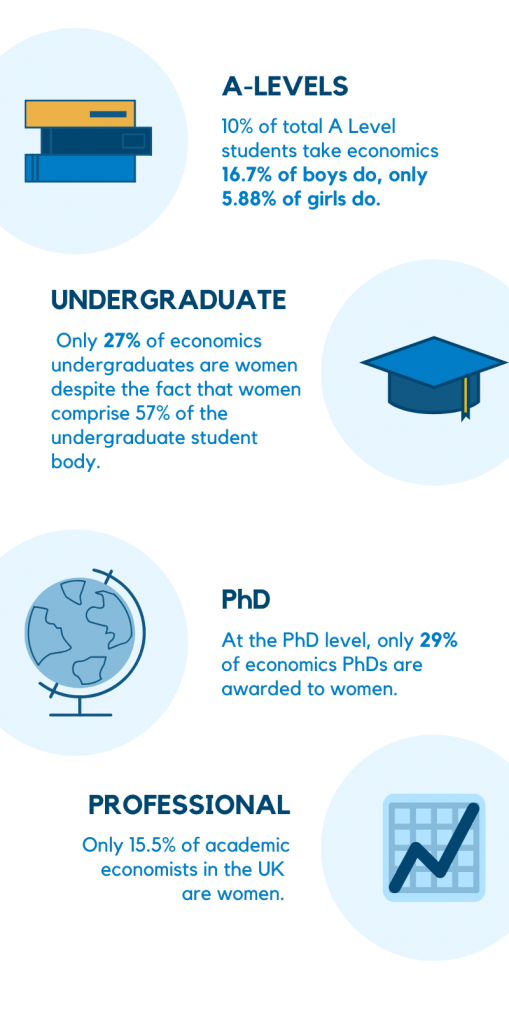

In the UK, while 10% of total students take Economics at A-level, only 5.88% of total female students do, compared with 16.7% of total male students (from World Economic Forum). Moving up the academic ladder, in a 2018 study it was found that while women comprise 57% of all undergraduates, they represent only 27% of the total undergraduate population studying pure economics (this figure is 33% if including degrees including but not limited to economics). Even in the early stages of higher education, women are less likely to pursue economics. Moving up even further, the representation of women in economics at the PhD level is even worse, with the figure hovering around 29%. Also important to note: this figure hasn’t changed for two decades. Finally, in the UK, only 15.5% of academic economists are women (from the BBC).

One of the biggest reasons for the underrepresentation of women in economics is that there exists a pervasive sexism in this professional field. In a recent study, Alice Wu, at the time an undergraduate at University of California Berkeley, created an algorithm that scoured online Economics Jobs Market Rumors forums for gendered language. It was found that while language about men was mostly “academically or professionally oriented,” language about women “ highlight[ed] physical appearance, personal information, and sexism.” Women are simply not respected in the industry in the way men are.

As well, it is reported that male economists, who hold the power within the field, are reluctant to admit that there is a problem. Thus, the process of hiring and recruitment isn’t changing.

Image by Lukas. Available on Pexels.

Economics is the foundation on which policy and business decisions are made by governments and firms. It determines where resources – money, time, labour – are allocated. Simply put, economic research shapes the world around us.

With this in mind, it is concerning that the body undertaking that research is so undiverse. In the words of FT’s Diane Coyle, “Does this [underrepresentation] matter? Yes. It is just as bad to have mainly male economic research and policy advice as it is to test medicines mainly on men. The results will fail at least half the population.”

What Coyle explains is that biased researchers will produce biased results. With men comprising the majority of the research body, there is insufficient attention paid to women and girls in data collection. Practically, without women in the room, the advice given to governments and firms reflects the experience of a mostly white, mostly male body of researchers.

Another reason why this underrepresentation is worrying is that there exists a difference in the way women and men address economic issues. In a 2018 study, it was found that “compared with male economists, women in the field have a greater tendency to look to government intervention for solutions, to support increased environmental regulation, and to perceive a gender gap in wages and other labor market conditions.” (May, et al. 2018) Without gender balance in academic economics, there is not ideological balance. The nature of the conversation is one of homogeneity and moreover, stunted progress in addressing the aforementioned issues of climate change, gender equality, and more.

Furthermore, women present less of an ideological bias to begin with than men do. In a study undertaken by University of British Columbia’s Dr. Mohsen Javdani and Cambridge University’s Dr. Ha-Joon Chang, it was found that men display certain biases when it comes to agreeing with given statements. When presented with the statement,

“Economics has made little progress in closing its gender gap over the last several decades. Given the field’s prominence in determining public policy, this is a serious issue. Whether explicit or more subtle, intentional or not, the hurdles that women face in economics are very real,”

not only did male economists disagree with more than women did, but their agreement changed based on who they thought the author was. When told it was written “by the leftwing British feminist economist Diane Elson, rather than the real source, Carmen Reinhart, a mainstream Harvard economist,” male disagreement rose. The way male economists navigate the field is not always with objectivity; Men present biases in a way that women often do not. Bias is dangerous, and as Coyle said, biased research will “fail” those it is not biased toward. In order to protect the integrity and importance of the field, it is imperative that women play a more prominent role in economics.

Including women in economics isn’t only an issue of addressing inequality in professional fields, it is one of necessity. Necessity for the balanced and unbiased consideration of global economic issues and those they affect.

Featured Image by Kris Krüg of Esther Duflo. Available on Flickr under Creative Commons 2.0.