At the beginning of this year Extinction Rebellion was included in an extremism guide where it is listed as a form of ‘ideological extremism’. The 12-page guide was produced by counter-terrorism police in the south-east as part of their ‘prevent programme’ to protect young people and adults from extremist indoctrination. The section on Extinction Rebellion was featured alongside neo-Nazi terrorism and Al Muhajiroun, an Islamist extremist group. Teachers and officials have also reported that the prevent programme has briefed them to look out for people supporting Extinction Rebellion and Green Peace. Since this story dropped on the 10th January in the Guardian police have reviewed and recalled the document however many have defended its inclusion.

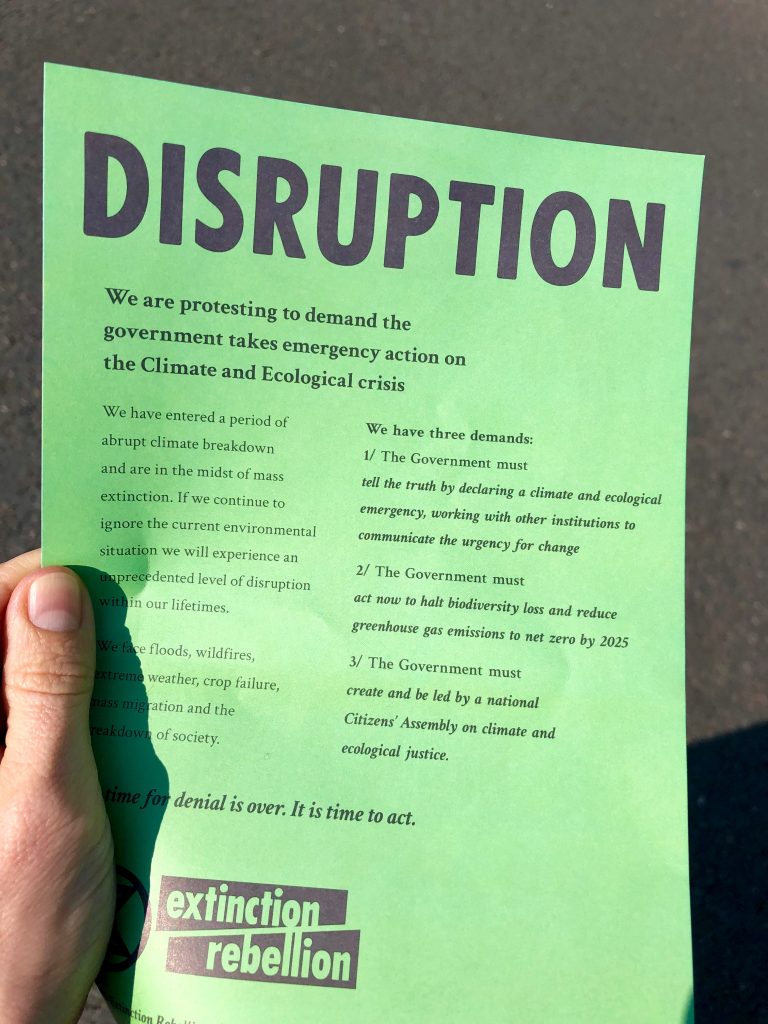

In the last year police have arrested thousands of extinction rebellion protesters and as of October 2019 it was reported that the organisation had cost Metropolitan Police £37m that year. Although Extinction Rebellion is a non-violent organisation their website describes their strategy as “non-violent, disruptive civil disobedience – a rebellion”. Extinction Rebellion’s strategy of being as disruptive as possible is what is making them noticeable where other climate protests have failed, however it is also alienating the very people it wishes to bring onside.

Then again peaceful protest has arguably failed. UK and world governments have known about the climate crisis for decades and have failed to act. Many politicians across the world remain staunch climate deniers and Boris Johnson is still refusing to speak on the issue. During Johnson’s 2019 election campaign he failed to show up to Channel 4’s climate panel and was replaced by a melting ice sculpture. But, is the disruptiveness of Extinction rebellion fundamentally damaging their image in the public eye? Or is it the necessary response to a crisis becoming more urgent with every passing day? This is the perpetual debate

The Climate strikes in September of last year, where protesters in London targeted bridges and tube stations, caused outrage among commuters. Protesters blocked five bridges across the Thames effectively shutting down the Thames district, and some protesters were reported to have climbed on top of tube trains. This has caused Extinction Rebellion to lose favour somewhat damaging their ability for mass appeal and therefore their effectiveness.

Yet, it is impossible to deny that the situation is now urgent. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, have reported that 2019 was the second hottest year in its 140 year climate record and NASA found that the last decade has been the hottest decade on record and despite this very little is being done. The disruptiveness of Extinction Rebellion’s protests is arguably proportionate to the level of crisis the world is now facing.

In their 2019 manifesto the Conservative party promised that the UK would reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Comparatively the Labour party in their 2019 manifesto promised to aim for Net Zero by 2030, and the Liberal Democrats pledged to generate 80% of electricity from renewables by 2030. The Conservative party’s goal of 2050 is therefore not sufficient especially considering that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2018 report leaves now only 10 years to cut global emissions by at least 45% to reach its target warming. The urgency exhibited by Extinction rebellion in its civil disobedience tactics can then perhaps be understood.

Home Secretary, Priti Patel has come out in support of the police’s labelling of Extinction Rebellion as ‘extremist’, citing that decisions were made on the basis of considered security threats and risk. Although Patel did concede that the group are a protest group not a terror threat.

However, columnists such as George Monbiot and Kevin Blowe, the Guardian, have argued that the labelling of extinction rebellion as extremist is not just unfair but wrong. Monbiot points to the long history of the UK labelling peaceful protesters as ‘extremist’ citing the case of Dr Peter Harbour in 2008 going as far as to suggest that those arguing that extinction rebellion is a ‘threat’ would have said the same about the suffragettes and Martin Luther King.

Extinction Rebellion has been a major inconvenience for police. The £37m it has cost Metropolitan Police is £37m that has not been spent reducing knife crime or tackling legitimate terrorist threats. However, Kevin Blowe argues that the very label of ‘domestic extremism’ has no legal definition and yet allows police to increase surveillance that could jeopardise the freedom of individuals supporting Extinction Rebellion.

A right to peaceful protest is a necessary right for a democracy to function. It is also the right of the police force to arrest those whose protesting activities break the law. The labelling of Extinction Rebellion as ‘extremist’ however is unjustified. Is it an extremist view to wish for the evidence of scientists and the reports from the IPCC and the NOAA to be respected and acted upon?

The November 2020 Climate Summit is to take place in Glasgow this year. Perhaps this the opportunity for the UK to take the leading role in tackling the climate emergency. To do this, though, our government and our Prime Minister must start to listen to rather than simply label views it does not want to hear.

Featured Image by Alexander Savin. Available on Flickr under creative commons 2.0 license.