Are US-style TV debates the way forward for British politics?

In 2010, the UK saw the first live TV debates between leaders of the main political parties, following the example set by the often game-changing leadership debates in Presidential elections in the United States. Across three debates, the leaders were invited by broadcasters to discuss the economy, domestic policy and foreign affairs, with millions tuning in. In the five years since, our political landscape has become even more dominated by social media; it appears that the broadcasters and the electorate want a repeat performance.

For that’s what live TV debates are: a performance. In a world where politics is often reduced to sound-bites, an electorate increasingly disengaged from politics may be encouraged by debate between the leaders; allowing them to present their party platforms directly to the voters may promote engagement and participation with the political process – especially with young voters, 42 per cent of whom, according to the Office of National Statistics, have no interest in politics at all. However, is this the best option British democracy has?

Firstly, the party dynamics of this political cycle make the three-way structure of the 2010 debates wholly redundant. The debate about the debates has seen a myriad of options raised and discarded; a four-way debate with UKIP included was vetoed by David Cameron if it did not include the Greens, then opening up the floor for the involvement of the SNP and Plaid Cymru, much to the fury of the DUP. Those who believe that debate allows voters to become more educated on the issues can hardly argue that this overcrowded playing field would make for constructive dialogue, rather than quickly descend into chaotic point-scoring between seven leaders all vying for camera time.

This is of special consideration for smaller parties like UKIP and the Green Party, who are likely to make bold claims in order to secure the largest segment of the anti-establishment protest vote once secured by the Lib Dems, without having to base the promotion of these policies in financial and legislative reality.

A format to include smaller parties would then have to be one in a series of debates, with second or third debates scheduled between those who are most likely to become Prime Minister. However, this then creates more logistical problems. Proposals for a debate between Cameron and Milliband as the leaders of the two largest parties would leave the Lib Dems unable to defend their record in office; but including a party with under 5 per cent nationwide support relative to the rise in other minority parties also seems counter-intuitive.

Even if the parties and the broadcasters could agree on a format for a range of debates; are TV shows the way we want our politics represented? Unlike in the US, the electorate are not selecting a leader or even voting solely for their preferred party, but making a decision about a local representative to represent them in Parliament. With local government elections already experiencing a dismally low turnout, this presidential-style of politics would draw focus away from local issues and further towards Westminster, enhancing the centralised establishment which so many voters feel is out of touch.

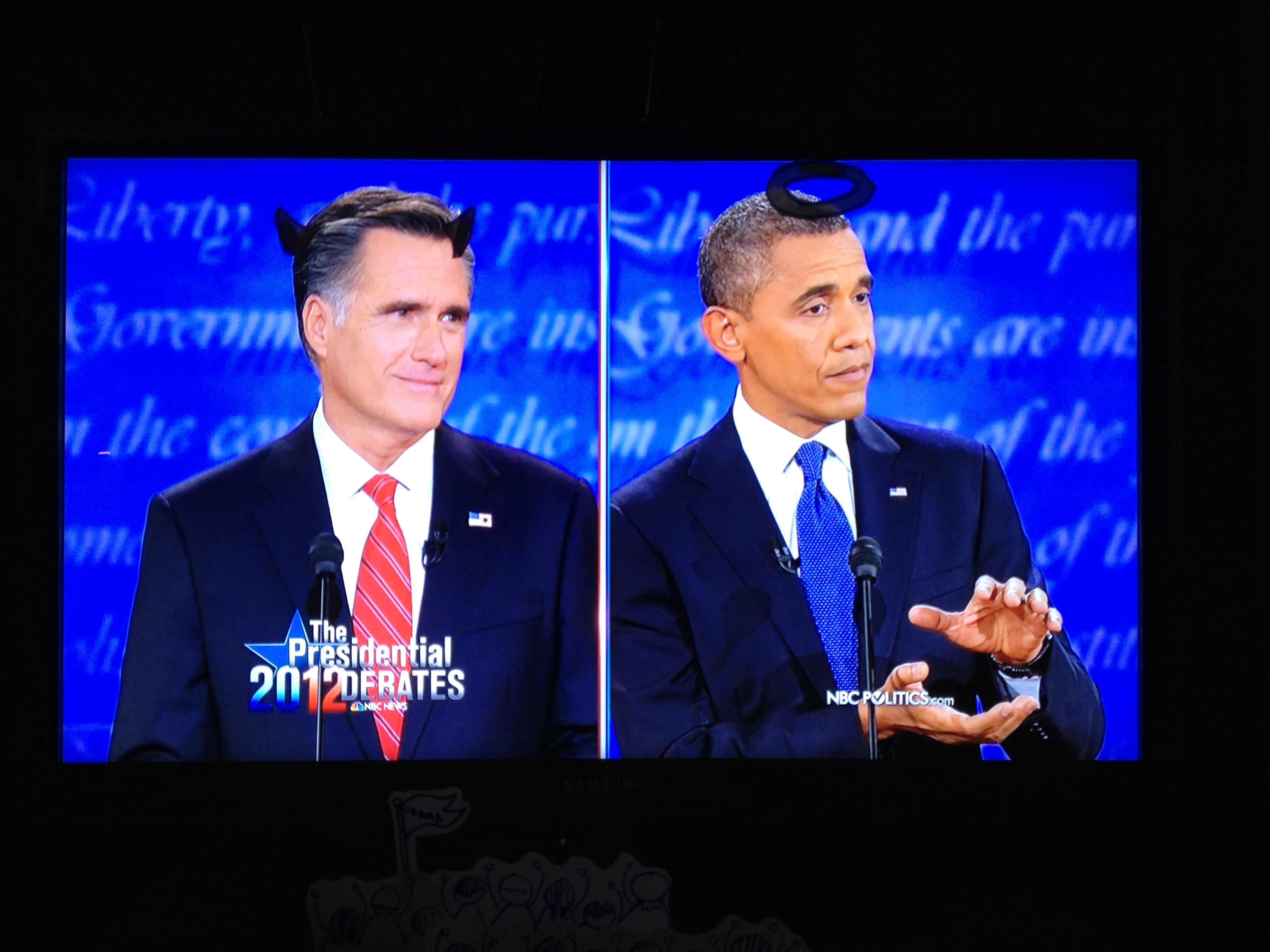

Similarly, would a rehearsed and well-prepared performance really provide the political education it claims to? In an image obsessed age of 24 hour news and instant opinion polls, in which political understanding is diluted down to 140 characters, creating a format that is all about the promises of one media-trained individual undermines true debate rather than enhancing it. The public opinion backlash against Obama throughout his second term has reminded us all of the gap been between rhetoric and reality; if debates become the primary source of political education, we will be electing the best public speaker rather than the best politician.

This undermining of real debate will only be enhanced by broadcasters focussed on ratings, increasing the likelihood that personal attacks and partisan squabbling would overtake any genuine attempt at a focussed discussion of the issues at hand. Politics is not a stage – presenting it as such skews general understanding of the cooperation and negotiation that makes up day-to-day politics, and give voters a false representation of the system. As newer, smaller parties divide the vote, the likelihood of coalition rises; Nick Clegg would warn of the consequences for leaders and parties of making promises that cannot be kept in the real world of Westminster, in which the absence of a majority of MPs in the House of Commons means compromise will be more necessary than ever.

Despite their promise to increase participation and promote politics, the debates are likely to do more harm than good in correcting the disease within Westminster. The desire for an open and negotiated debate is now more likely than ever to descend into political point-scoring between party leaders more focussed on capturing headlines than keeping promises. A debate focussed on presidential-style leaders undermines the Parliamentary system and creates a false impression of the realities of government and legislation, in which voters may opt for a charismatic orator rather than a local MP that will listen to and represent their concerns. Whilst reaching out to younger voters and embracing new forms of media is essential for politics, reducing the entire political process into three hours of politicians squabbling is not the healthiest way to restore faith in British democracy.