Two first years offer two very different verdicts on new Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn…

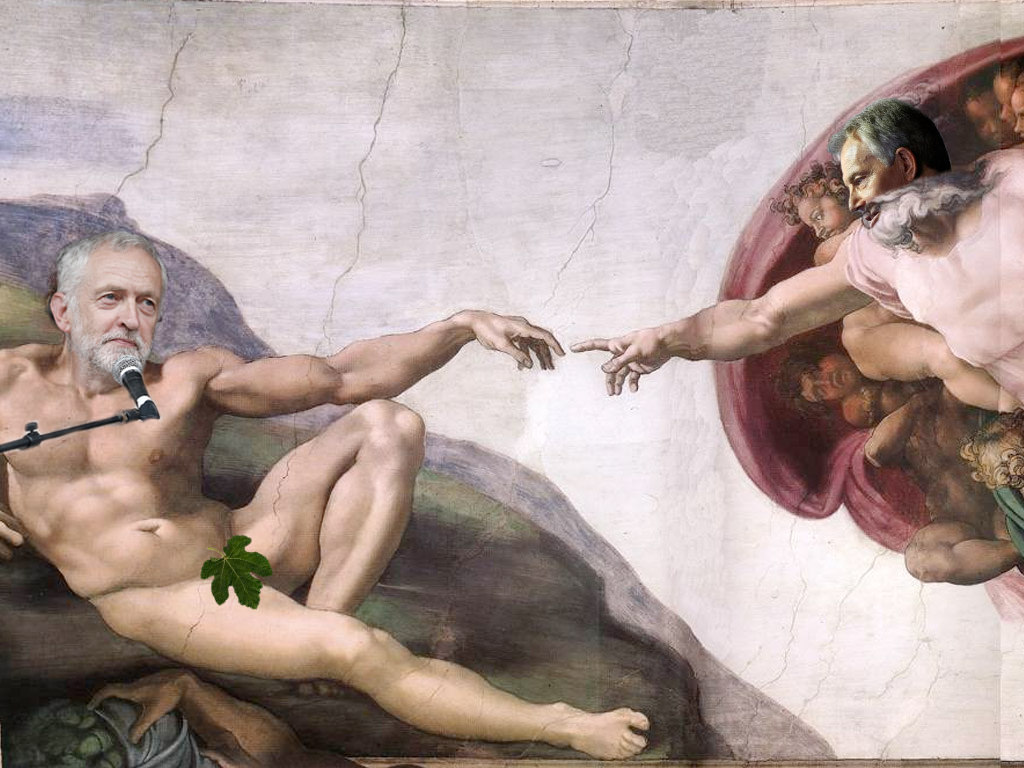

The Creation of Corbyn…

Daniel Cohen

Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader of the Labour Party has been termed by pundits and politicians alike as the greatest leadership election upset in a generation. Despite receiving some support from young people during the contest, Corbyn is not offering us anything that will actually be deliverable.

Corbyn has not put forward any proposals either during his leadership election campaign or during his tenure as leader thus far that resembles a plan for the future; his ideas are outdated and will not benefit those growing up today. Instead of spelling out innovative proposals, he is more content with collating old-fashioned, Clause Four policies such as nationalisation of industry that were even considered out of date when he entered Parliament in 1983.

Indeed, successive general elections have shown that parties considered to be ‘bring backers’ simply do not win; they have to have a fresh, positive vision for the country and be able to connect with the majority of people’s wants and needs; Corbyn’s platform, for now at least, is far too narrow to appeal to a majority of the electorate. Although polling suggests some of Corbyn’s policies do have a degree of popular support, this hasn’t been reflected in the voting tendencies of the country as a whole, who have consistently and explicitly rejected the extreme left agenda in every general election since 1974.

Indeed, given the collapse of Scottish Labour and the grip of the SNP, in order to win an election Corbyn would have to make gains in the midlands and the south of England; seats not even won by moderate centrist Tony Blair. Nor will Corbyn likely be able to allay young voters fearing the breakup of the United Kingdom, as his London-centric ideas could act as a barrier to reaching out to Scottish voters too.

Moreover, young people are innately able to see through political posturing and reach their own conclusions, and even many young Corbynistas cannot refute the claim that the Labour party is divided – a party which cannot weave together a convincing and harmonious narrative come election time is doomed to fail. People want to know where they stand with a political party. They want to be able to place their faith in their ability to deliver both stability, and their manifesto promises. This is of course especially important for young people entering the jobs market – economic stability is key, and this would be no guarantee with a bitterly divided Labour government. While the term ‘the economy, stupid’ is sometimes too narrow to wholly analyse election victories, it is nonetheless the case that Labour were perceived as deficit deniers and far from credible managers of the economy under either Gordon Brown or Ed Miliband. It therefore seems bizarre to suggest that Corbyn and his Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell – who proclaims that one of his hobbies is the overthrow of capitalism – could win back the trust of the electorate.

So not all young people view Jeremy Corbyn as a messianic figure, and those who don’t share his views should not give in to the pressure of doing the supposedly moral thing and supporting him. Instead we must continue to promote popular capitalism and the free market as the most effective way to generate prosperity.

Alannah Travers

Our writer Alannah Travers cosying up to Corbyn!

Unsurprisingly, I wholeheartedly disagree with Daniel’s view. Whilst he undeniably states some truths – Jeremy Corbyn’s election victory was indeed the greatest leadership election upset in our generation (although Ed’s comes a close second), and the Labour party does appear increasingly divided at the helm – Corbyn offers a brilliantly fresh approach to politics which should be embraced, not eschewed.

How dare he claim Corbyn’s ideas are ‘outdated’, or critique McDonnell’s economic credibility? Jeremy has smashed the political mould to smithereens, truly standing for issues such as ending austerity and protecting workers’ rights (in stark contrast to Cameron’s current position and Milliband’s half-hearted attempts); as well as opposing all welfare cuts, campaigning to scrap tuition fees and reigniting the cry to nationalise the railways and utilities. Advocating abolishing Trident and withdrawing from NATO may be complex and controversial, but it most certainly isn’t same-old.

Equally, in a letter to which David Blanchflower (a former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee) is a signatory, the accusation that Jeremy Corbyn and his supporters have moved to the extreme left on economic policy is also disputed: ‘his opposition to austerity is actually mainstream economics, backed by the conservative IMF… he aims to boost growth and prosperity’. Efforts to paint Corbyn as an economic extremist are therefore greatly exaggerated as a smear on a man elected in the most democratic leadership election the Labour party has ever staged.

Daniel’s claim that Corbyn is not offering anything deliverable to young people, too, must be challenged. Speaking recently to Radio 1’s Greg Dawson (his first broadcast interview as Labour leader, illustrating his priority to communicate with younger voters), Corbyn vowed ‘to change Labour party policy so we don’t end up penalising people for getting educated, leaving young people with massive debts… raising the minimum wage to £10 so they have some kind of chance in life’. (How does this not offer anything to university students?!) How can it be claimed that Corbyn offers nothing to students when so many of his policy priorities directly benefit the young people that were so instrumental in electing him?

Finally, Daniel’s view that Corbyn will fail to win in 2020 because his platform is too narrow to appeal to the majority is also completely misguided. Of course, pessimism is entirely understandable; Burnham, Cooper or Kendall, too, would have faced a difficult task, needing to bring Labour back from the brink in Scotland, and having to battle against sly Tory boundary changes in England, but it is Corbyn who offers the best chance of winning support from across the political spectrum. The Labour party under Corbyn has the liberal policies needed to win back dissatisfied SNP, Green and Plaid voters, and consistent YouGov polling claims that 73% of those who voted UKIP in May actually back rail nationalisation, whilst 52% support rent controls and 66% want a living wage. Ultimately, Labour needs to win back those who voted Tory not by out Tory-ing them, but by offering an alternative. In my view, Jeremy Corbyn is absolutely the right person for this job.

Are you doubting Daniel or agreeing with Alannah? Have YOUR say in our poll