This week, in what can be assumed as an explosive expression of Christmas cheer, David Cameron announced a review into the most festive of all topics; the use of firearms by UK police. In the wake of the Paris attacks, the government is looking into existing legislation to review definitions of “reasonable force” in order to reduce police hesitation in responding to terror attacks. A cynical person might view this as an attempt to cement the government’s portrayal of the Labour leader as a “terrorist symapthiser”; a jibe thrown out by the PM during the Syria battle that may look increasingly true in the face of Corbyn’s opposition to “shoot-to-kill”.

However, let’s maintain the starry-eyed optimism that a politician would never use such a serious topic as a political plaything, especially given that Corbyn seems to be imploding nicely, this is probably a legitimate government policy and not a shot at the opposition (pun intended). As seen across the Atlantic, the issue of police use of force could not be more serious; both morally, logistically and mostly importantly, in terms of the relations between the public and the police that underpin the security of any state. Should the police be shooting to kill?

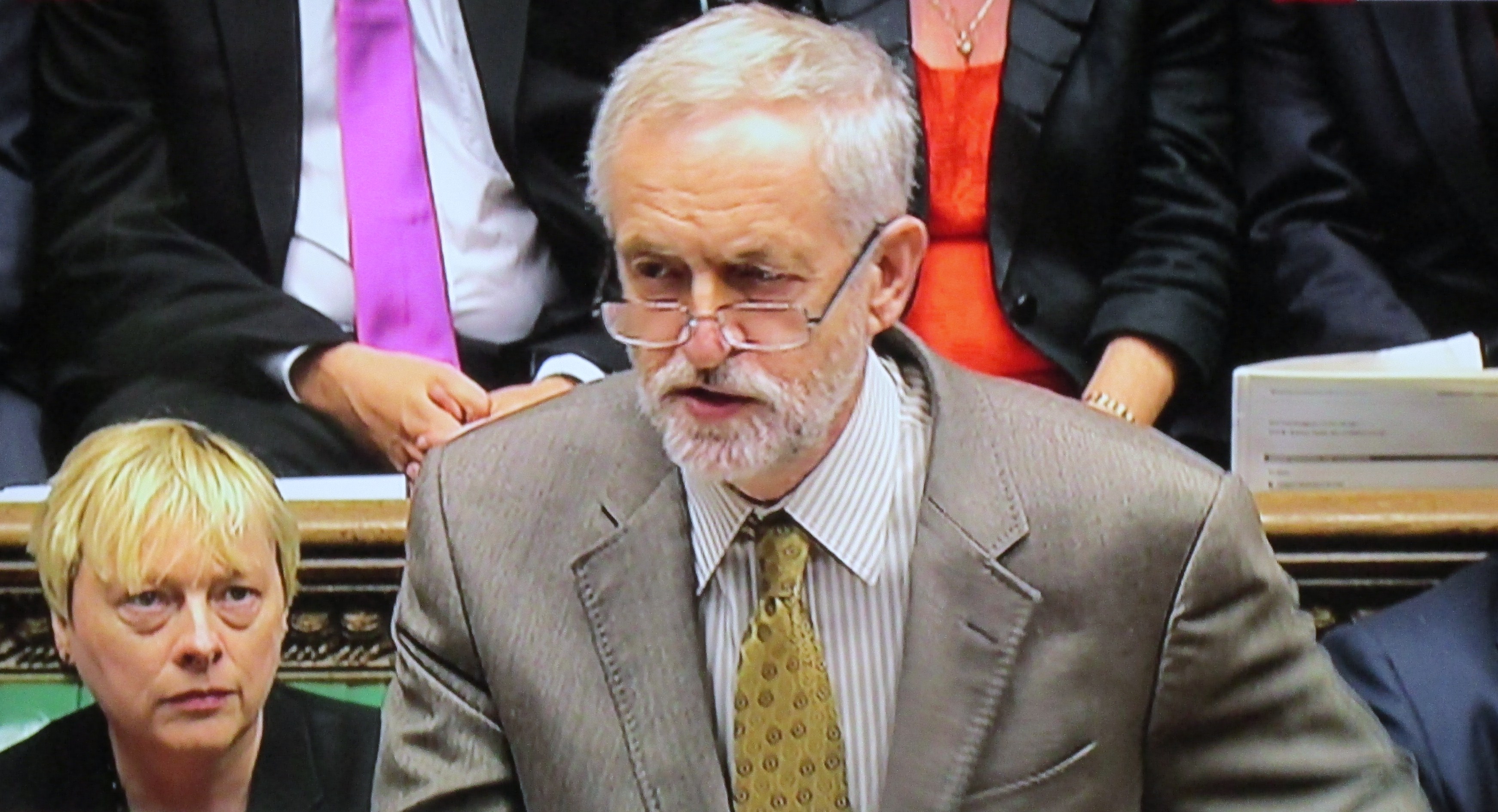

Corbyn and Eagle: divided over firearms

In what has become the main pre-occupation of most of the parliamentary Labour party, shadow business secretary Angela Eagle attempted to mitigate Corbyn’s views, stating we should give “our armed police the confidence if they are dealing with a marauding terrorist…they can get that person down and save life”. On first glance, this reflection of the governments intention makes sense; remove legal barriers to give police freedom on the ground to make urgent decisions required in emergencies to prohibit an attacker and avoid the destruction seekn in Paris. On the surface, this seems like an open shut case.

However, removing reigns on police use of firearms sets a serious precedent. Existing legislation permits use of force in situations of self-defence, defence of another person, property or to apprehend a crime; the rhetoric invoking Paris makes clear that this review concerns ‘terrorism’ specifically rather than your average criminal. Therefore, the logic follows that in order to shoot-to-kill, police would have to be both willing and able to instantly judge whether a situation could be considered a ‘terror’ attack when facing a criminal at the scene. Defining what is and is not terrorism in a court of law is already murky territory, so the concept of placing this burden of proof on active police is surely even more suspect.

Even if we accept that police are able to make this distinction and communicate it clearly at the time, this still leaves open questions as to the use of force. Whilst police do a difficult job in a high pressure situation, the concept of officers taking the time to evaluate their decisions to end a life in a moment of panic does not wholly seem like a terrible idea, even if they are doing it to avoid lawsuit rather than for the sanctity of human life. The police response to the Leytonstone tube attack, a Taser, arguably had the same is not a preferable response to a bullet. The man was apprehended and can now be questioned by police, potentially aiding a wider investigation into preventing further such radicalisation, prosecuted through the courts and served justice in a manifestation of the very system that the ‘war on terror’ is supposed to be upholding. Is that not better than creating another martyr in the mosque and a body in the morgue?

It is on this point that “shoot-to-kill” becomes an issue about more than individual criminals and officers. If the police gain legitimacy to extend the use of force, the ramifications of this will be more violence; both from officers with greater security in their actions and by civilians, who may be threatened by a stronger enemy into preemptive force. It takes no time to look across the pond to America, in which the firearms capability of police has done little to reduce the violent altercations between both armed and unarmed citizens; a society that permits the police to kill its citizens will find a lot more of them dead.

Midlands police: armed but not firing

America offers the UK another warning in examining the relationship between law enforcement and the public, particularly in poorer or minority communities where violence is endemic. The use of force by police has resulted in institutionalised racial profiling of minority Americans, in which black Americans are a shocking SEVEN times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts. The backlash against this has been mostly peaceful in protest, but has also sparked riots and revitalised racial tensions and police brutality across the country.

In fractious times such as these, where it is already easy enough to equate terrorist activity with particular ethnic groups, the last thing the UK needs to be adopting from the Americans is a violent dimension to our homegrown divisions. Reports of corruption and cover-ups in cases from paedophiles, prostitutes and plebs alike have already diminished the reputation of British police, which is undermining the trust of the public that is essential to the legitimacy of the state. As with Syria, this review seems to be sparked from a widely shared sense that ‘something’ must be done; but as the Lib Dem leader Tim Farron (who, in fairness, could say anything he likes without anyone really noticing) said, the law ought to be reviewed in “a calm and collected manner, not in a knee-jerk response to terror attacks”.