AI is rapidly becoming an issue for the energy industry, with its power demands ballooning in size. Morgan Stanely estimates that global data centre power use will triple this year, from ~15 TWh in 2023 to ~46 TWh in 2024, and Wells Fargo predicts that AI power demand will increase 550% by 2026 (from 8 TWh in 2024 to 52 TWh) and another 1,150% by 2030 (to 652 TWh). To put this in context, this would mean that Data centres would use 8% of US power output by 2030, as opposed to 3% in 2022. This is something that the energy industry was unprepared for, and many tech companies are being backed into a corner after making public promises to meet renewable energy goals prior to the boom in AI.

What is the solution to this rapidly increasing demand for power, whilst meeting these sustainability goals? Well Big Tech seems to think that Small modular reactors (SMRs) are the answer.

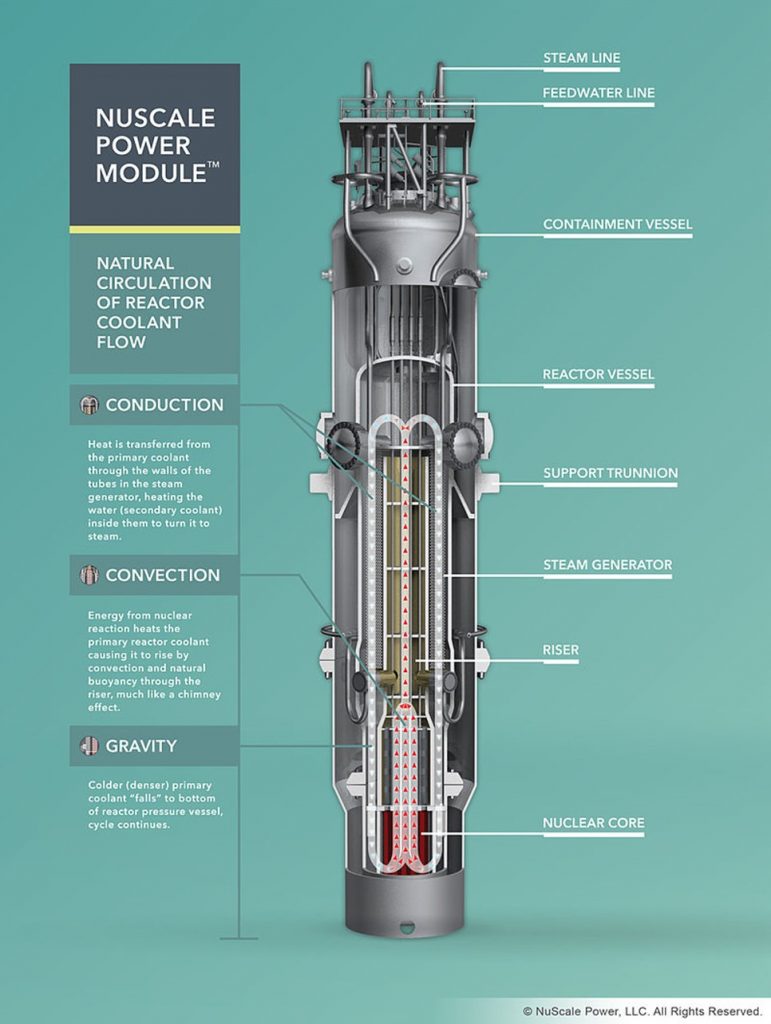

So, what is an SMR? Today’s large scale commercial reactors produce approximately a billion watts of power, whilst SMRs would produce less than a third of this. However, due to their smaller scale, upfront costs would be hugely reduced (this has been the main issue holding back the construction of new reactors) and hence uptake of nuclear power would accelerate. In addition to this, the smaller reactors have reduced safety concerns as the small power output means less residual heat to cool in order to safely shut down the reactor.

The energy demands of many industries could be met using these, thanks to their modular nature. By combining modules (each produces a couple hundred Megawatts of power) the differing energy demands of different industries can be met. Their smaller size also means they can be constructed offsite and shipped to the desired location, as opposed to commercial reactors, which require building on site due to their scale.

A diagram of the plan for the NuScale Power Module reactor (50 Mwe), which was scrapped in 2023. The image was provided to Wikipedia by NuScale directly.

The interest of Big Tech in this emerging technology was made clear in October, with Google announcing its partnership with Kairos Power, to purchase nuclear energy from them, and Amazon investing over $500 million to develop SMRs with X-Energy. Furthermore, the CEO of OpenAI himself, Sam Altman, is backing OKLO (another company focussing on the research and development of SMRs), with Altman acting as the chair of the company.

But will this investment pay off? The history of this industry implies that the road ahead may not be as straightforward as it seems. The first US plan for a SMR was the mPower project, which was launched in 2009, and should have become operational by 2018, however it was terminated in 2017 after its costs doubled from the expected. The US company NuScale is another good case-study. In 2016 they announced plans to build their first module for $3 billion by 2024, but these initial estimates shifted over the project’s lifetime to $9 billion by 2030, and the project was eventually terminated in November 2023.

The reality is that only 3 SMRs are currently operational (2 in Russia and 1 in China) and all three ended up costing at least 3 times more than expected and their construction took at least 3 times longer than planned. The SMR currently under construction in Argentina is faring even worse, with it having now exceeded 7 times its planned cost. So, one of the main positives of the SMR, its small upfront cost, has been shown to be inaccurate in many cases. It is hoped that with the large investments being poured into this industry, that these costs will come down as the technology is refined. However, the shear abundance of companies in this sector may serve to slow the research, with money being spread over many possible options rather than backing a select number of candidates.

Whether SMRs are the solution remains to be seen, but the support of both tech companies and governments (more than 25 countries are now investing in SMR) will only serve to aid in the exploration of this new and emerging renewable energy source.

Featured photo was made by combining an image of the Tennessee Valley Authority Nuclear plant, obtained from the Tennessee Valley Authority on Flikr, and the amazon icon, by Canonicalized on Flickr.