18 February 2019

20:44

In November, Chinese scientist He Jiankui prompted global condemnation after he revealed to a stunned conference audience his use of the latest gene editing technique to permanently alter a set of twin girls’ DNA. Through releasing a YouTube video and exclusive press release Professor He explained his choice to use the CRISPR-Cas9 system to reportedly prevent HIV transmission in several hopeful couples, with a third baby on its way. Clouded in confusion and controversy, the events have stirred up debate around the use of CRISPR on human cells and the ethics around the concept of gene editing.

What is CRISPR-Cas9?

CRISPR is a molecular system used in bacteria to prevent viruses from targeting their genes, discovered by two research groups groups in 2012. When combined with the Cas9 guide molecule it can be engineered to work in human cells and cut DNA at a chosen gene location, where it could disable a faulty copy or supply a healthy copy of the gene. So far, the technique has been used briefly in very early embryos which are only maintained for a matter of days, or more widely as a gene therapy method for modifying genes in body cells, such as to treat lung cancer. Its use on cells such as sperm, eggs and new embryos is a form of so-called germline editing. This technique has not been performed in humans until now due to tight regulations, since modification in the genes of such early cells could then be inherited by future generations ad infinitum – carrying with them any unconsidered dangerous consequences or even mistakes.

Why was the Treatment Controversial?

Alongside the fact that Professor He proceeded aware of these risks inherent in germline editing, several other factors contributed to the scandal surrounding his announcement. Primarily, the claims have not been published in a peer reviewed paper yet and therefore their validity remains very much under question. Moreover, the researcher’s reasons for editing the chosen genes seem dubious; since the children’s father was HIV positive, Professor He chose to disable the CCR5 gene before IVF implantation in their mother’s uterus since this change would block the HIV virus from infiltrating the children’s immune cells, preventing transmission of the burdensome disease. However, there are existing medical methods which can reliably prevent transmission of HIV from father to child without risking such an imperfect gene editing method. The CRISPR system is far from faultless, with off target effects reported in some studies meaning that genes other than the chosen target may be unintentionally altered, potentially even prompting cancer development.

What were the Consequences?

Dubbed the Lulu and Nana controversy, Professor He’s decision to edit the genome of these children has been criticised both internationally and in China. His university, the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, has claimed it was unaware of his project and launched an investigation into his practices. His work was illegal under Chinese laws which state that human embryonic stem cells may only be used experimentally for 14 days – in stark contrast to a full term pregnancy. The New York Times has reported that despite some speculation that the Shenzhen government contributed funding to his research, criminal charges for He now seem likely following a governmental investigation. The long term effects on the children born with the edited DNA remain to be seen.

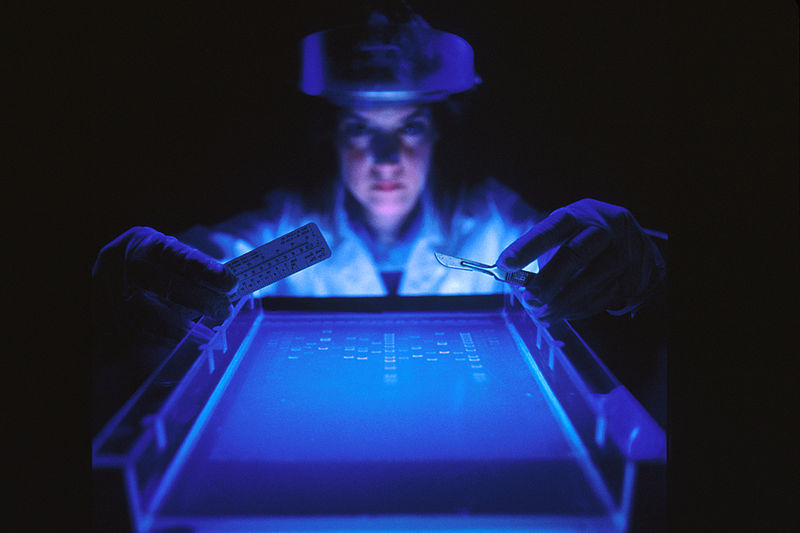

Image source: Flickr. Courtesy of the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability.

What does this mean for the Future of Gene Editing?

Countless reverberations were felt across the scientific community in the aftermath of Professor He’s actions. His decisions to experiment on germline human embryos and his choice of gene target were met with wide disapproval. Ethics expert at the University of Oxford Professor Julian Savulescu described it as ‘monstrous’ and 122 Chinese scientists issued a joint statement condemning He’s experiments in addition to more generalised direct human experimentation.

Other experts have nonetheless taken other perspectives. George Church, a Harvard geneticist, spoke with Science shortly after the revelation to argue in favour of a more nuanced position. Church supports He’s choice to target the CCR5 gene, the HIV infection point, claiming that it makes more sense than the main targets of many CRISPR researchers. These targets are generally mutations at one point on the gene, like sickle cell anaemia, which could be edited with ease – but Church claims that these diseases can actually already be prevented by simply choosing to use embryos without the mutations during IVF. He also argues that there is no evidence of negative consequences of off-target accidental DNA ‘hits’ from CRISPR, stating that “at some point, we should start focussing on the health of the babies“.

While the event has underlined the necessity of caution and regulations in germline editing, and the scientific community should be praised for its response, more importantly it has highlighted the great need for preparation. We cannot simply wait for perfection with gene editing techniques, and once the evidence of benefits can outweigh the evidence of risks of the procedure for patients we are obliged to implement them. When we reach this point, it is crucial that science and society have jointly directed the development of clear gene targets to treat with explicit potential to cure chronic diseases, definitions of the distinct boundaries bordering augmentation as opposed to treatment to prevent the fabled phenomenon of designer babies, and foremost watchful worldwide enforcement of experimental regulations.