Fossilised remains of a 10-meter-long sea creature were found in Rutland Water, UK. This unexpected discovery has sparked interest in the life of the Ichthyosaur marine reptile (or ‘sea dragon’) that lived 250 million years ago.

In February 2021, Joe Davis of Leicestershire and Rutland Wildlife Trust stumbled across a 10-metre-long sea creature fossil in Rutland Water Nature Reserve (the largest reservoir in the UK). The endeavour was only recently unveiled due to concerns that its discovery would prompt a raid on the site—fossils are lucrative objects, so all attempts to conceal its whereabouts were necessary.

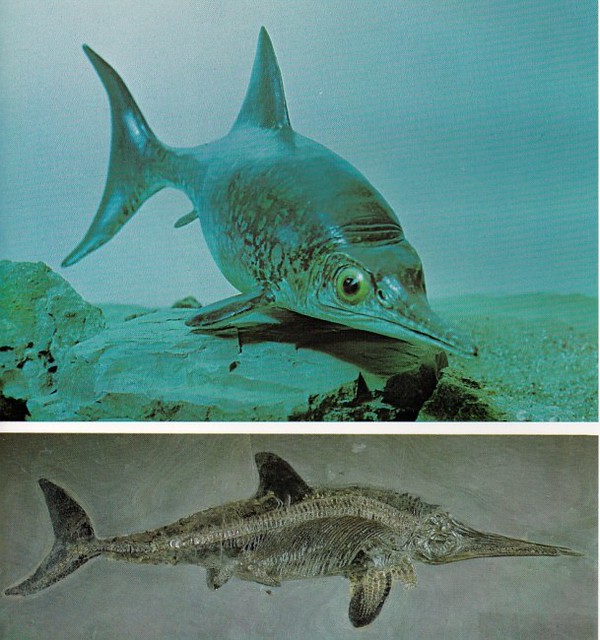

Upon publicising its discovery, experts reported that it was the most complete skeleton of its kind found in the UK, measuring as 33ft (10m)—making this discovery highly significant. The fossil’s shape was long, with observers noting its corporeal similarity with dolphins.

Commenting on the discovery, palaeontologist Dr Dean Lomax said that “It was an honour to lead the excavation.” He explained that Ichthyosaurs originated in Britain and although many skeletons of this kind have been found, this one is the largest and most complete fossil. “It is a truly unprecedented discovery and one of the greatest finds in British palaeontological history.”

The fossil is currently being studied and conserved in Shropshire but there are plans to move the fossil back Rutland to be displayed. Academic papers are expected to be published in the future, with palaeontologists set to continue researching the newly found remains.

The Ichthyosaurs: what, where, when?

Ichthyosaurs encompass any extinct group of aquatic reptiles—many species are similar to porpoises both visually and in habitat. Ichthyosaurs is the genus from which species sub-groups stem from. They are often misconstrued as dinosaurs, but they were in fact the most highly specialised kind of aquatic reptiles.

Their existence almost completely spans the entire Mesozoic Era (251 to 65.5 million years ago), but they were most prominent during the Triassic and Jurassic periods (251 to 145.5 million years ago). Skeletal remains have been found in southern Germany, including the outline of a well-developed dorsal fin, but nothing compares to the discovery at Rutland Water.

It is thought that they could move through the water at very high speeds, were fish-like in appearance and could not survive on dry land. Adaptations included a streamlined body and no distinct neck, with the head streamlining smoothly into the body to enable faster swimming. It propelled itself through the water using its paddlelike limbs and a well-developed fishlike tail. The bent condition of the backbone became apparent through well-preserved evidence. Nostrils were located far back on the skull as a key adaptation for an aquatic existence. It is thought that they fed upon fish and other marine animals, predominantly as an ambush predator. The eyes were extremely large, which is thought to have allowed them to better see large shapes—often scanning for potential predators such as the Pliosaurus—some way in the distance. All species became extinct well before the end of the Cretaceous Period (the last of the three parts of the Mesozoic Era).

Why did they go extinct?

Crucially, a huge threat to Ichthyosaurs was the Pliosaurus; with long bodies and an impeccable swim speed, they were a danger to the Ichthyosaur. As its specialisation became more apparent over time, this specie of predator was said to have reached 15 metres in length.

When explaining the history of the Ichthyosaur, Dr Valentin Fischer of the University of Liege, Belgium and the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Oxford said, “we compared the diversity of Ichthyosaurs with the geographical record of global change”. Fischer explained that Ichthyosaurs were actually ‘well diversified’ with ‘several species, body shapes and ecological niches present’.

However, their evolution was too slow to keep up with their ever-changing environment. The effects of climate change, such as rising temperatures and sea level change, made it increasingly challenging for Ichthyosaurs to adapt to their surroundings in order to survive and reproduce. Despite the reasons for extinction being elusive and conjectural, it is also thought that competition with other marine predators and thus a decline in their principal food source contributed to their extinction.

Featured image: Ellis Owen with licence