“What’s to say that they’re just dreaming and we don’t hear the noise? Image by Christopher Cook, Flickr under Creative Commons Licence

Trigger warning: This article contains references to suicide, and suicidal ideation, if you or anyone you know is affected by this, please contact help:

Samaritans- 116 123

Nightline numbers can be found on your campus card/Duo.

Have you ever had that feeling? Just one perfectly normal day, you’re walking down the street and you cross over a bridge, or you look over the railings and you see the drop below. Completely within your wits, or you think you are, and all of a sudden you get that voice shouting in your head. Watching the plunge below as a phenomenon of human creation, knowing the outcome that would come from the step over, that voice comes and cries out in your mind. Maybe a piercing whisper, maybe a silent cry of desolation, but heard clear as day-

“Jump!” it says.

Then as soon as you catch it, you take hold of your senses once more and it disappears, as if it was never anything more than a passing fancy. It doesn’t mean that you would ever do it, it doesn’t mean that you would even give it serious consideration, but the thought was definitely there. What would it be like? How would it feel? Imagine if it happened, what would you do?

Weird right?

If this phenomena is completely alien to you, then we can look to the experience of others.

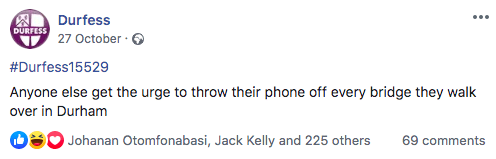

Whilst the 200+ reacts of #Durfess15529 might not be a definitive scientific study, it is a feeling felt by many and for some it will feel familiar, this doesn’t mean that there’s anything wrong with you- quite the contrary as research suggests.

Maybe it says to jump off the edge of a high building just out of curiosity, perhaps it says to yeet your phone of Kingsgate Bridge, or two-footed tackle a toddler, or kiss your lecturer as you walk into the Calman, just to know what would happen. This has a basis in science. This phenomena even has a name. Rather ominously, it’s been titled the Call of the Void and rather than being the band that you chose to listen to during your angsty teen rebellious phase, it is a phenomena that has been studied by psychologists.

What’s to say we’re not all screaming but you can’t hear our voice? Image by bobistravelling, Flickr under Creative Commons Licence

A 2012 study from Jennifer Hames at Florida State University called it the ‘High Place Phenomena’ and in a sample of 431 students, almost a third of them noted that they had felt it with over half of those who had experienced it noting that they had never had any suicidal tendencies. As well as the 30% who reported they had the urge, 53% of the sample reported that they had imagined jumping off a high building or bridge, affirming the prevalence of the scenario in the lives of regular students, but also leading to the question of why is this happening? Why do we have the thought of taking a step to experience a fall into the unknown? What is the driving force behind this?

Reddit user ‘travers’ in the thread ‘TIL “call of the void” is that feeling when you think for a second about steering into oncoming traffic or jumping off a cliff for no reason although you would never do it’ described it as “Your brain is just doing a system test, making sure you decline the suggestion,” simply an alpha test for the most complex software in the universe. Hames’ paper reports that this is some kind of miscommunication within your brain- it is simply, “fear circuitry, subserved largely by the amygdala.” Simply put, when you are on the verge of a dangerous scenario such as a high bridge or building, your fear circuitry is aware of this and is sent into action, sending a rapid signal to your brain alerting you of the danger leading to the reflex action of ‘take a step back, you might fall off the edge’, so you do, it’s in your best interest to stay safe but the safety signal is relayed so fast without you even thinking about it that when you respond, you question yourself. ‘Why did I do that?’ you wonder. ‘I wasn’t close enough to need to back up?’ you consolidate, and this chain of thought leads you to a few moments later try to conceptualise it and this safety signal gets misattributed to the conclusion of ‘I must have wanted to jump, or at least thought about it’. Whilst it’s true that the thought at least crossed your mind, it was merely as a warning rather than a prompt.

Relax.

A call to the void, or l’appel du vide is simply an affirmation of your will to live, the desire to preserve the insatiable human appetite for life.

An alternate theory was offered by Adam Anderson of Cornell University. Rather that this leap of logic at least is rather an extreme and counter-intuitive display of risk aversion. The innate tendency of gambling in the face of risk is on display here, similar to how if you’re a thousand pounds down on the poker table, you’re willing to put more in to try to win back your losses, you place a greater value on avoiding present loss than you do on future gain. So being on a high building with a fear of heights, you know that the ground below is the safest option, the desirable option, thus you feel the pull of the quickest way there. It doesn’t make sense as taking that option would cause your demise, it tackles the panacea of being at a height. “We solved the fear of heights problem: jumping. Then we are confronted with the fear of death problem. It’s like the CIA and FBI not communicating about risk assessments.”

This all has to do with cognitive dissonance, your brain has not the capacity to deal with the conflicting signals it’s receiving. Consider Gordon Ramsay recommends you a restaurant, objectively a trustworthy culinary opinion, however when you visit, it is awful- the food is poor, the service is a myth, you ask to speak to the manager and the organisational structure might as well have left you stranded in the middle of Germany. These two conflicting sources of information- the anecdotal and the lived experience- disagree with each other so you bridge the gap by saying they were having a bad night. Or that a Christian who all their life has believed that only Christians can go to heaven but befriends a Muslim student at university and having been exposed to their beliefs now has to re-evaluate their own to compensate for the untenable position of having to believe their friend might not go to heaven. Or even growing up in school being taught you shouldn’t ever use ‘I’ in essays, or never start a sentence with ’and’ or use a comma with it. And maybe even that to end a sentence with a preposition is objectively wrong and something that should not be put up with. Only to reach a higher level of education and all of a sudden, your politics, English, and history lecturers all tell you something different about these rules- you don’t want to betray the often personal relationship one has established with your school English teacher yet this new information betrays that education. These relatively banal examples of not knowing how to handle conflicting signals is the same principle that makes you step back from the edge of the bridge, even if there’s a guard rail in between you and the fall- the gap between step back to avoid the fall and I’m not close enough to fall is where the patch of ‘I must have wanted to jump’ comes in. Rather it’s the urge to avoid a non-existent threat which reaffirms the anxiety induced nature of this belief, making you worry about a problem that doesn’t exist. This also shows the correlation of the research of Hames between those who have experienced the call and those with anxiety.

So what happens if you listen to it? This has been documented on the reddit thread of “People who have succumbed to “the call of the void”, what happened?” and if you’re reddit user ‘mahboilucas’ whose call to open the door of the car on the motorway led only to castigation- “I opened my car door while on a busy highway when I was 13. My mom got mad and shouted at my dad to stop the car on the side to close the door.”

For IronSlanginRed, the call was to just lean forward a bit too far on a chair lift, resulting on an anti-climactic plummet into the snow- “Fell off the chairlift. Was leaning forward just watching and just kinda went off. Wasn’t very high but it did hurt a bit falling 20 or so feet onto snow.”

For this now deleted account, it went even further:

“I explored an abandoned hospital last year, which had two towers with 10 floors. These towers weren’t that far from each other but not an easy jump.

I stood on the roof of one, enjoying the view and whatnot and something started to… I don’t know what. In a matter of seconds I sprinted and jumped roofs. I was not pleased with myself. I love heights but I hate being near an edge – jumping over it was so against my instincts I was really shaken.”

The fear, the voice that we all dread, the silence still calls to come.” Image by Stella Dauer, Flickr under Creative Commons Licence

This malfeasance of almost illogical actions is linked to the idea of ‘intrusive thoughts’ or the ‘throw the baby impulse’, perhaps most commonly known by the metaphor from the Edgar Allen Poe short story- The Imp of the Perverse. David Wegner of Harvard University explained this with the example of the forbidden thought. Quite simply, it’s that old game you play where you tell yourself “don’t think about penguins,” and suddenly all you can find yourself doing is thinking about penguins. Before thoughts of the Gentoo, the Adelie, or the Two-Spirit penguin never crossed your mind, now it’s all consuming. Part of your brain needs to think about what it is you need not think about to be able to repress the thought of it, so paradoxically, to not think about penguins, you must think about penguins, after all how else would you know not to think about them. Your brain is then confused by this request and compounds it by now only thinking of that one thing and this theory is the same in the larger scale of wanting to drift off a chairlift or flash at the front of Christmas formal. You are constantly repressing thoughts of things that you shouldn’t be doing, and every so often, that imp slips out and preoccupies your mind- whether for a passing moment or persistent minute, this acts solely as a sign that you now that doing it would be wrong.

The constant pressure on your brain to be of eternal high performance makes it inevitable that these thoughts will slip out every so often, after all we are only human, every so often the software needs a patch and that’s what learning is. It isn’t a call to be alarmed, but rather a fire drill, a call that if it comes to it, you are alarmed. Not having these thoughts creep out isn’t a problem, and the same goes for having these thoughts creep out too, it simply shows that you’re alive, and you know it. And you want to keep it that way. It’s just that little check every so often that the batteries don’t need changing, unfortunately just like a fire drill, and often inconveniently, your brain doesn’t always let your body know that there’s a test incoming.