The shortage of major news stories during an international break makes it the ideal time for publishers to release their clients’ autobiographies. Harry Redknapp, updating his once again, Rio Ferdinand and Roy Keane have all been at the forefront of the sporting agenda over the past few days as extracts of their books have been serialised in national newspapers.

Keane’s book was always likely to raise the most eyebrows, and generate the most controversy. Redknapp is such a keen talker that there is very little new information in the updated version of his autobiography. Ferdinand, similarly, has already been forthright in his opinions, making his feelings quite clear on the race row involving John Terry that brought English football to a standstill.

Yet, Keane grabs attention in a way that neither of those two would ever be able to. It is a testament to the size of his character, as well as the respect he commanded as a player, that he remains a figure of such fascination. Anybody else with as undistinguished a managerial career up until now, as Keane’s, would barely be given the time of day, encouraged to continue his apprenticeship as a number two before coming out to criticise others.

In the years gone by, most people would have been unable to name the assistant manager of Aston Villa, never mind have rushed to the bookshop to ensure they got their hands on a copy of his book.

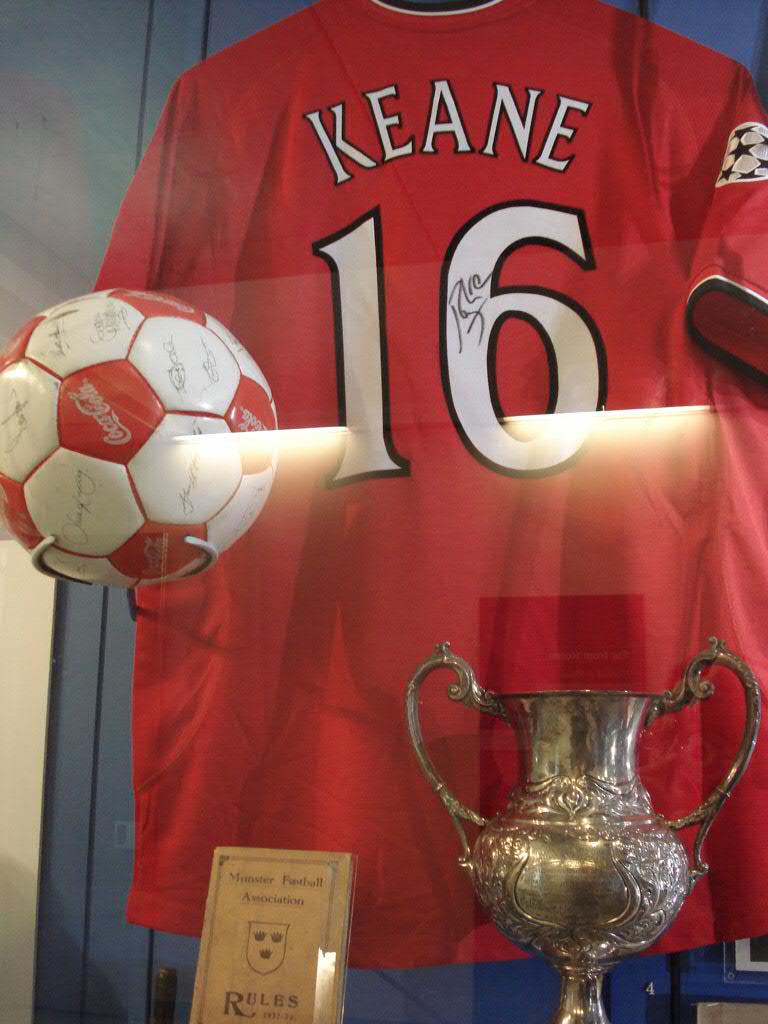

With Keane, we are talking about one of the finest players of a generation, not just a serial winner with Manchester Unite. He is an integral part of a great side, captaining for many years from the heart of midfield. Keane can get away with having achieved very little since then because his playing success has bought him plenty of time, giving him a certain amount of credibility when taking on established and well-respected people in the game, figures such as Alex Ferguson and Mick McCarthy.

It is a long time now, nearly nine years to be precise, since Keane’s acrimonious departure from United. Even so, there is an enduring interest about the way things ended, a curiosity that stems from the fact that the circumstances remain disputed by those involved. Keane insists that Ferguson had it in for him after an angry training-ground bust-up with assistant manager Carlos Queiroz, whilst Ferguson’s account is based on the infamous interview Keane gave with the club’s in-house television station in which he allegedly gave a damning assessment of his young team-mates.

The truth is probably somewhere in the middle; that Keane left because, aged 34, his legs were starting to go, and his outburst gave Ferguson the excuse he needed to dispose of a deteriorating player. The details are unlikely to be as exciting or dramatic as many of the sensationalised media portrayals based only partially on the two men’s accounts, but there is a mythology about Keane’s departure that continues to elicit interest.

Perhaps it is because neither Keane nor United have been able to move on. Nearly a decade later, Keane is still bitter, not quite as furious as some of the serialisations have made out, but nonetheless hurt and indignant about the way he was ushered out of the door. Indeed, you have wonder whether Keane has ever recovered from the blow, retiring after an underwhelming few months at Celtic before enduring hit-and-miss spells in charge of Sunderland and Ipswich.

Keane would dispute that, of course, pointing to how he got Sunderland promoted in his first season, taking over a team on a losing streak and instigating an impressive recovery. His time at Portman Road was an altogether gloomier episode. Few doubt that Keane has the experience or the intelligence to emulate his playing achievements in management, but it is about whether he still has the desire or hunger to do so. Keane looks and sounds perpetually angry, as if he feels the whole world is conspiring against him.

By the same token, the saga rumbles on because United have never quite managed to replace him. They are in a different era now, in the midst of a transition, albeit an extravagant one, under Louis van Gaal, but the most expensively assembled team in the history of English football could still benefit enormously from a player in Keane’s mould. Even when they were winning successive Premier League titles and competing in Champions League finals on a regular basis, United lacked that battle-hardened core to their midfield offered by a truly talented, tenacious tackler in the centre.

Keane’s great asset was that whilst he primarily rampaged around the pitch looking to disrupt the opposition, he could also damage them with his own technical ability. Paul Scholes, already on the wane by the time Keane left, was never the same again without his reliable partner alongside him. But for Keane’s insatiable appetite for victory, the class of 92, players like David Beckham, Gary Neville and Ryan Giggs, might have lacked the edge they developed whilst playing with a natural leader on the pitch.

The absence of talking points during this fortnight without Premier League football has allowed us to take a nostalgic trip back in time to fascinating events involving Keane and United. What is striking is how relevant they remain today, both for the former player and the club. It cannot be dismissed entirely as a coincidence that they have each been lacking something ever since.