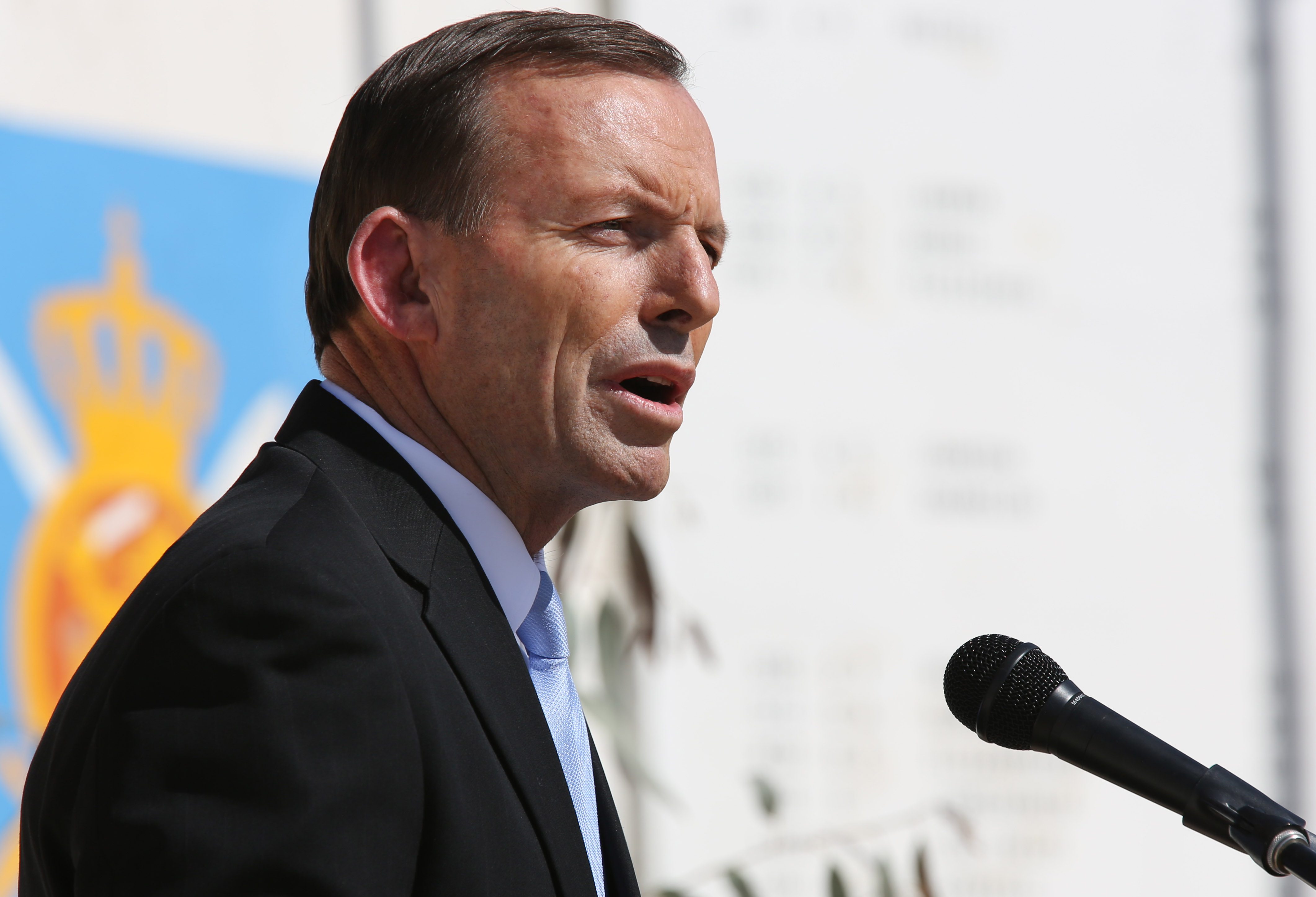

Tony Abbott, former Australian Prime Minister recently ousted by Malcolm Turnbull, was noted for his hardline approach to immigration.

Over the summer the news was dominated by the refugee crisis in Europe, with the numbers of boats crossing the Mediterranean from North Africa causing major problems in Greece in particular. Chaos on the island of Kos, typically a thriving tourist destination, was beamed into living rooms across the world. 10,000 miles away in Australia, migrant boats have been a major political talking point for years, and the country’s policy on what to do about them changed very recently, with extraordinary results.

When the recently-departed Prime Minister Tony Abbott came to power, Australia had a far more lax policy about accepting asylum seekers via boats. In 2013, 20 000 asylum seekers found their way into Australia via boats, typically being picked up by the Australian navy and then taken ashore. It has been claimed that under the previous Labor governments, 50,000 migrants on 800 boats had made it to Australia. There has been increased tension in recent years between Australians and immigrants, with the Croa race riots of 2005 shocking the world and proving that there were major problems between the Australian and immigrant communities.

A survey by the Australian National University has shown that immigration is seen as the second most important concern for voters. As a result, Tony Abbott made a radical ‘stop the boats’ pledge in his election-winning campaign of 2013 and clearly proved popular with the Australian public. Under Abbott’s system, whereby turnbacks of migrant boats were controversially implemented, the number of migrants entering the country by boat was reduced to just 157 in 2014, with 20 reported turnbacks since the implementation of the policy in 2013. These boats are either sent back to Indonesia, or if the occupants are deemed to be refugees, they will be escorted to detention centres on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea or Nauru, and once processed, would be resettled in one of Papua New Guinea, Nauru or Cambodia. It has been made clear to immigrants through governmental messages that they would not, under any circumstances, be allowed to settle in Australia.

One of the main hopes of this new, strict policy was to restrict the number of boats risking the perilous journey in the first instance, and the fact that there were only 20 turnbacks in 18 months shows the success in that. Lives have inevitably been saved as a result and brutal people-smugglers are being put out of business. The question can then be asked in light of Australia’s success; can the EU countries facing the current crisis learn from the way that Australia has dealt with their boat problem?

There would certainly be widespread support for such a policy from across Europe. The UK has already withdrawn support for naval rescue operations in the hope that it deters people from making the journey. If there was success on the same level as was seen in Australia, an immeasurable weight will have been lifted off the region.

Inevitably, there are problems that exist in Europe that don’t in Australia. It is possible that the tough sanctions in place in Australia have exacerbated the situation in Europe with Australia no longer a viable option. It is also possible that with the sheer volume of migrants coming to Europe, an Australian system designed for managing smaller numbers would not work. Australia has never had to deal with the near 600 000 migrants that have entered Europe by boat this year alone.

Cost is also a major potential barrier – the detention centres in PNG and Nauru cost Australia AU1 billion annually. The cost of that in Europe would be significantly more given the volume of people, and would be a cost that Greece would never be able to meet, and a sum that the EU would likely struggle to raise considering the inevitable controversy that it would create.

The reality is unlikely that EU countries would be able to do anything similar. The UN and other refugee campaigners already oppose Australia’s policy, with questions remaining over its legality under international law. It is likely that the European Court of Human Rights would block an Australian-style policy in Europe on those grounds. Already in the past, a deal brokered between Italy and Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya to send back immigrants who made the journey to Italy in 2012 was deemed a breach of human rights by the court, and in 2011 migrants were not allowed to be sent back to Greece by other EU states on account of their possible inhumane treatment as a result of their disastrous asylum system.

The problem in Europe is clearly too big to be ignored, with something needing to be done quickly. While mirroring Australia’s system exactly looks to be off the cards for various reasons, the system Down Under has shown the world that a hard-line approach can indeed have immediate and impressive effects and you can’t help but wonder whether even some aspects of their system could be adopted in Europe.