The beheading of Thomas Paty in Paris last month was abominable, and yet the under-reported atrocities committed in northern Mozambique at the start of November dwarf even that vicious act of terror.

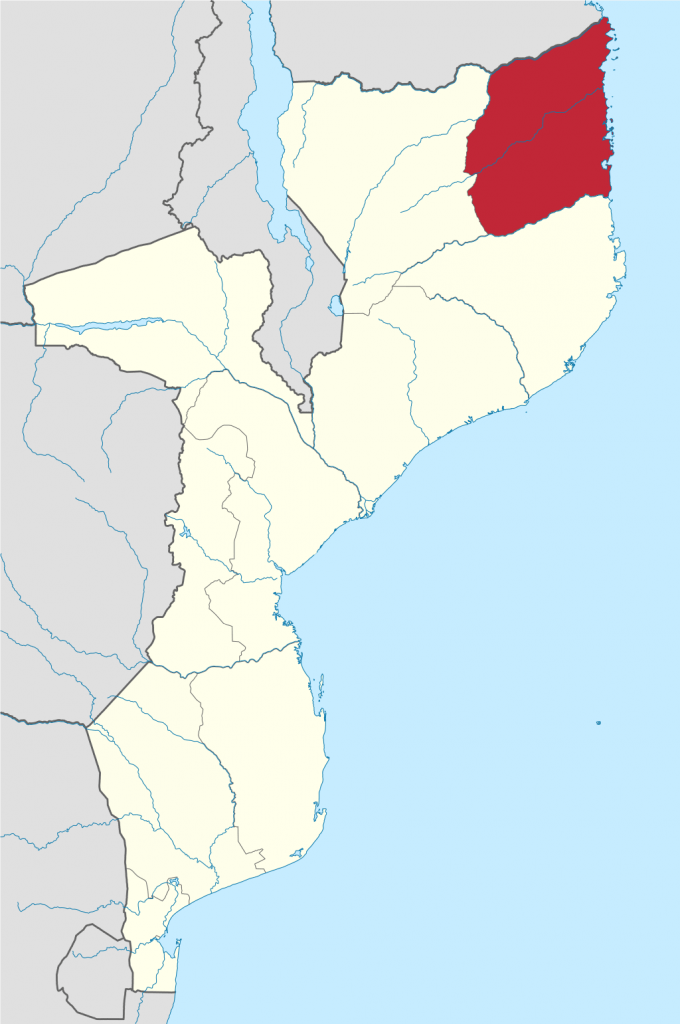

Two weeks ago, in perhaps the most horrific crime committed anywhere in the world in 2020, up to 50 men and boys were beheaded, their corpses dismembered, and their village laid to ruin by militants linked to the so-called Islamic State. Even more disturbingly, this is not the first attack of its kind to take place in the Cabo Delgado region in recent years, near Mozambique’s border with Tanzania. Nor will it be the last.

Cabo Delgado province (red) within Mozambique, bordering Tanzania to the north and the Indian Ocean to the east (Source: Profoss on Wikimedia Commons).

Since a strong and well-organised Islamist insurgency broke out here back in 2017, there have been over 600 attacks and more than 2,000 deaths, the majority being civilian casualties. As a result of the violence, at least 355,000 people have fled their homes, many seeking refuge in neighbouring Tanzania and provoking an international humanitarian crisis.

The entire continent is experiencing a revival of Islamist extremism. From Mali to Kenya, Nigeria to Libya, militant groups connected to offshoots of the so-called Islamic State in western, central and eastern Africa threaten the already fragile political orders of several states. Just as significant a force is Al-Shabaab – the infamous extremist faction in Somalia – who also appear to be involved in many of the flare-ups in eastern parts of the continent. In Somalia’s neighbour and powerful rival in the Horn, Ethiopia, ancient fears of Muslim occupation are resurfacing as part of a growing ‘civil war’ discourse surrounding the conflict in northern Tigray province, not least as a result of the furtive influence of Al-Shabaab.

Above all, however, Mozambique stands out as both a present and future stronghold for militant Islamism in Africa. Cabo Delgado, its most seriously affected region, bears many of the hallmarks that enabled the so-called Islamic State to establish themselves in western Iraq and beyond in 2014. Rich in both oil and natural gas deposits, the area contains more than enough economic potential to support a proto-state. Its population, on the other hand, consists overwhelmingly of impoverished subsistence farmers, who are close to defenceless, even with the token support of understandably terrified police and military units.

Although nominally in a state of peace since 1992, Mozambique has been beset by fluctuating cycles of violence and futile poverty for decades. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), in its most recent Human Development Report, ranked Mozambique as the 10th least developed country in the world. Perhaps more strikingly, if Cabo Delgado were a country itself, it would be the 3rd least developed nation globally, behind only Central African Republic and Niger. This latest episode of mass killings is shocking, but in a debilitated country like Mozambique, terrorist attacks in a far-flung frontier province are not even close to the top of the government’s agenda in Maputo, the capital.

Unknown Islamic State fighter in Niger – picture taken by a US military operative during the Tongo-Tongo ambush in 2017 (Source: U.S. Army Special Forces on Wikimedia)

The reality is that terrorism is often more of a Western preoccupation than an African or, in this case, Mozambican one. It is telling in itself that, for most readers, this article will be the first they have heard of anything going on in Mozambique; unfortunately, stories of entrenched poverty don’t sell papers quite so well. Of course, journalistic impulses are not necessarily cause for criticism, as it is precisely the media traction gained by this kind of story that prompts foreign governments to intervene.

But would an international response improve the situation?

After error-strewn campaigns by Western forces in Iraq, Libya and Syria in recent years, we know only too well the ambivalent impact of foreign military involvement on both local populations and the powers involved. Particularly when faced with the guerrilla-like opposition of Isis-related forces, victory may become untenable. To take a current example, The Economist recently called France’s continuing counter-insurgency efforts in Mali “unwinnable but still valuable”. If indeed ‘unwinnable’, then it is difficult to see where the ‘value’ lies and for whom, especially if Malians must continue to live in fear. One must also question President Macron’s true motives for intervention, although genuine altruism for these people seems unlikely.

More promisingly for Mozambique, developments facilitated by the African Union have provided at least a glimmer of hope: Tanzania’s head of police has finally agreed to support its southern neighbour in tackling the terrorist threat and it is hoped that other states will also get on board to resolve what is quickly becoming a pan-African issue.

Obtaining the cooperation of local actors in this way is positive news and signals the determination of African nations to solve African issues, without the need for foreign entanglements. While a bitter pill for the West to swallow, perhaps this is the only viable way to halt the rise of a new and increasingly fearless Islamic State.

Image: F Mira on Flickr.